Pali basics

language

Pali is the modern name of the ancient language of the Theravāda Buddhist scriptures. The earliest Pali texts are the Tipiṭaka, and in addition there are many commentaries and other works in Pali.

Pali is one of the languages that were commonly used throughout northern India in the centuries BCE. It is related to Sanskrit, but has a simpler and more colloquial spelling.

pronunciation

The pronunciation of Pali is described in detail in ancient texts. Ancient Indian linguistics is one of the most precise of all social sciences, and the texts details the exact methods of pronunciation and places of articulation in the mouth.

Modern pronunciation of Pali varies according to the linguistic background of the speaker. For example, speakers of a dialect that does not include both “r” and “l” might confuse them in Pali. Retroflex consonants, which are pronounced with the tongue curled back on top the roof of the mouth, are absent in most languages and are usually replaced with the corresponding dental. Sometimes the same letter is used for different sounds in the local language than in Pali. For example, ภ is pronounced as aspirated “p” in Thai, but as aspirated “b” in Pali.

Despite these regional variations, scholars agree on the original pronunciation.

script

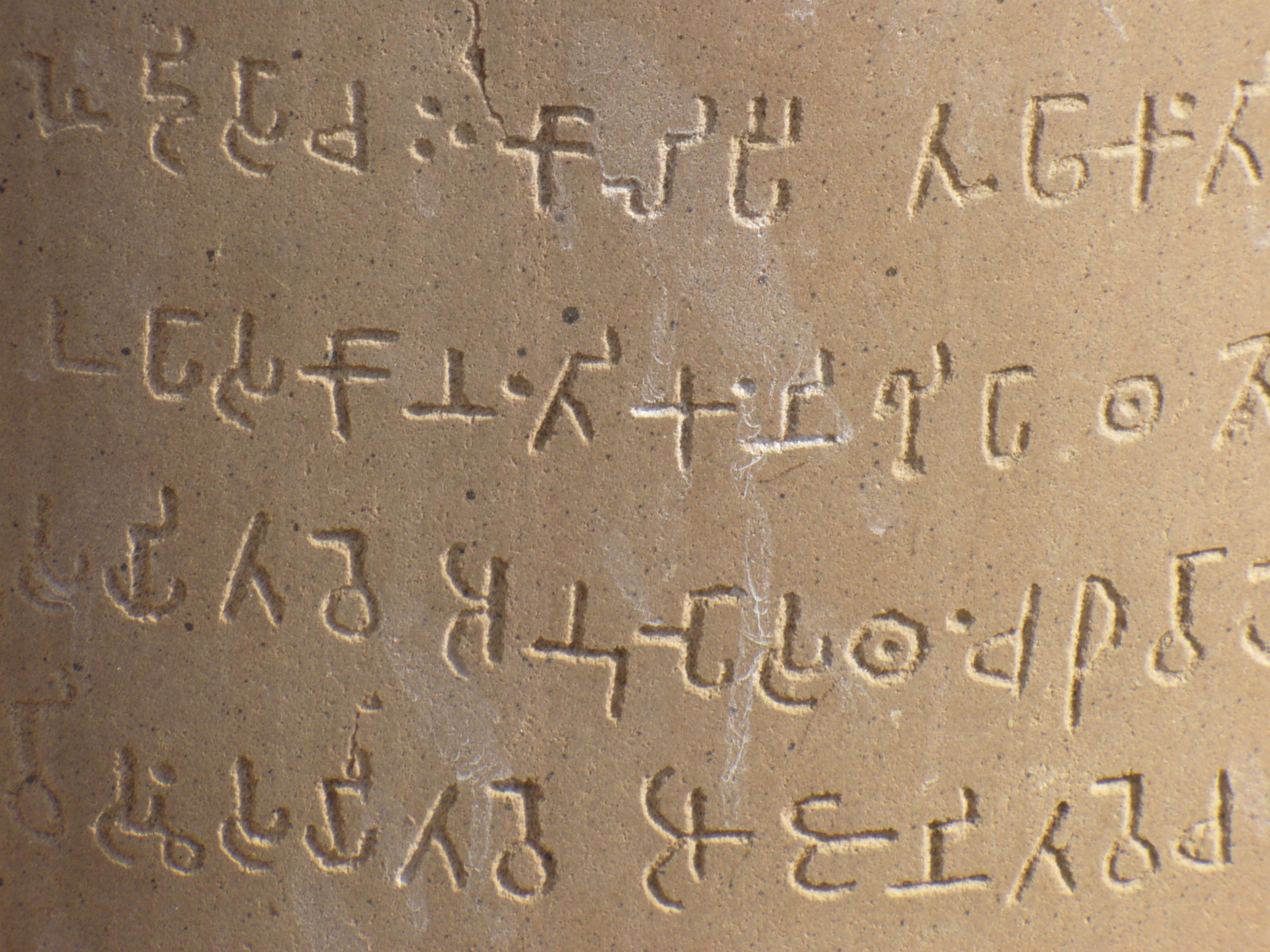

A script is a way of writing down language. Written Pali uses a variety of scripts. Like all Indic languages, the writing system is phonetic; it represents exactly the elements (akkhara) of the language as pronounced. For this reason, Pali may be written in any script that can represent the phonetic sounds. There is no therefore no “correct” form of Pali script.

The earliest written Pali texts would have been in Brahmi characters, but none surive from the earliest times. However they would be very similar to the Ashokan inscriptions in the closely-related Magadhan dialect, written in the Brahmi script.

Later, Pali was written in a variety of scripts such as Sinhala, Myanmar, Khmer, or Thai. In 1894 European scholars settled on the IAST system of transcribing Pali, which uses the Roman alphabet with some diacritical marks to represent certain sounds in Sanskrit and Pali. In 2001 the very similar ISO 15919 standard was adopted as an international system of romanizing several Indic languages including Pali and Sanskrit. It is worth noting that there is no historical evidence of Pali being written in Devanagari.

As with pronunciation, there are local variations in romanization. This is because the romanization conventions for the local language are different than that of the Pali, a subtlety that can cause confusion for those who do not understand language. For example, in Sinhala, sujato is romanized as sujatho.

Pali consonants are described in a systematic way depending on the place of articulation in the mouth, moving from the back to the front. Each place of articulation has four stop consonants depending on whether it is unaspirated or aspirated; and an additional nasal. The following table shows the Pali consonants (except the glottal h) in three commonly-used scripts: romanized IAST or ISO 15919, Thai, and Sinhala. Due to the precision of these systems, the Aksharamukha script converter used by SuttaCentral can convert over 90 scripts.

| velar | palatal | retroflex | dental | labial | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stop | nasal | ||||||

| voiceless | unaspirated | ||||||

| aspirated | |||||||

| voiced | unaspirated | ||||||

| aspirated | |||||||

| fricative | |||||||

| approximant | central | ||||||

| lateral | |||||||

manuscripts

Pali texts come down to us in the form of palm-leaf (ola) manuscripts. These are hand-inscribed with an etching tool, then died with ink. Because they are hand-written, each manuscript has errors and eccentricities.

In the tropical countries where Theravāda flourishes, palm-leaf manuscripts rarely last more than a few centuries. Thus virtually all Pali texts are edited from palm-leaf manuscripts that date to the 18th or 19th century. There are very few instances of Pali older than this.

Internal evidence suggests that the transmission of manuscripts is fairly exact, since editions in different countries differ only trivially. To test this, SuttaCentral is digitizing the oldest Pali manuscript, a 13th century copy of the Cullavagga from the Colombo Museum.

text

A “text” is an abstract idea separate from a particular edition of the text. The Tipiṭaka is perserved in multiple specific forms (palm-leaf, paper books, stone blocks, digital text, digital audio files, even human memory); each of these forms may have many editions; and each edition may have many copies. Multiple people may memorize the same text, or different sets of books containing the Tipiṭaka may be published.

Therefore there is no single “Tipiṭaka” and there never has been. It is an idea to which all the editions in different forms approximate. While each edition will invariably have variations, when these are checked across different editions, the variations turn out to be very minor.

The diversity of sources attests to both the continued interest in the Tipiṭaka and the exacting standards of those who have created the many editions.